I had the opportunity to attend both the talk "Two Nanyang Styles" by Kwok Kian Chow and the 100 Years of Singapore art exhibition at the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre (SCCC) yesterday.

I had the opportunity to attend both the talk "Two Nanyang Styles" by Kwok Kian Chow and the 100 Years of Singapore art exhibition at the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre (SCCC) yesterday.

Lit Review: https://observer.com/2023/06/singaporean-artist-georgette-chen-sets-three-auction-records-in-less-than-one-year/ Singaporean Artist Georgette Chen Sets Three Auction Records in Less Than One Year By Alexandra Tremayne-Pengelly • 06/01/23 2:04pm

Auction headlines

that get into the news are sooooo about money. If you read them, they highlight

the movement of money. Most of the time, this kind of news is about how much

money the art was sold and how much it has risen in its financial value. There

will be little about art's other values. You know, pictorial value, beauty,

social value, whatever. Hence the only thing we are sure of in this kind of

news is its exponential 'surprising' - rise in financial value.

Thanks

to Jeffrey Say for highlighting this piece of news about Georgette Chen’s

auction success (Tremayne-Pengelly). This lit review is not a critique of

money and art speculation. Instead, I want to unpack thoughts around it by following

the money.

Before this auction,

somebody sold and bought 2 of Chen's paintings each for $1.6 million and nearly

$1.5 million in November (2022) and August (2022), respectively. This sale of

$1.8 million is the 3rd time Chen's auction record has been broken — the sales

total to about USD 4.9 million. There is no mention of who sold and bought the

work on these 3 auctions; we don't usually know when big sums of money are

changing hands.

Chen's painting was

auctioned at Christie's Hong Kong. Evelyn Lin, deputy chairman and co-head of

the 20th and 21st-century art department at Christie's Asia Pacific, claimed

that the May auction saw sales worth USD 160 million. Based on a quick search

on Christie's auction records, I found USD 137 million from 3 auctions on 28

& 29 May 2023. Chen's painting was auctioned in one of these auctions on 28

May at the 20th/21st Century Art Evening Sale. That auction saw consolidated sales

of art worth USD 92.5 million worth of art.

Noting the rise in

financial value, the author points out the influx of 'wealthy' immigrants

during the Covid-19 pandemic as a reason for the surging growth in its art

scene. Surging growth seems ambiguous, but I read it as rising financial

resources from new immigrants during the Covid-19 pandemic (2020 - 2023). The

author also points to increasing demand for Southeast Asia art based on

Sotheby's first auction in more than 15 years, as Southeast Asia accounted for

nearly a 75 per cent increase in its global sales over the past five years.

Some preliminary search

shows that the increase in demand is based on this 28 August 2022 auction in

Singapore which was a 'resounding' success achieving USD 18 million (Singapore). It is the highest

total for any sale held by Sotheby's in Singapore --- ever. Comparing to the

Christie’s auction of 2 days, Sotheby’s ‘demand’ in financial value (18 million

vs 132 million) is much less.

According to the

article, there is an increase in 'appetite' for million-dollar works where

Singaporean collectors spend more than $1 million on artwork rose to 25 per

cent in 2022, compared to just 4 per cent in 2019 as quoted from the report

from Art Basel and UBS. In addition, the median expenditure on artwork also

increased, with $322,000 spent last year compared to $129,000 in 2021 and

$93,000 in 2020. At the time of writing, I was unable to find and rectify the

data claimed here.

However, Singapore

is noted a few times in the report. As the review is an exercise to follow the

money. I have extracted other ‘money info’ related to Singapore. One of this is

Singapore’s double-digit growth in auction sales driven by Sotheby’s sale of

Modern and Contemporary art (McAndrew, p188). Asia (including Singapore) accounted

for almost 20% of global auction sales at USD 1.1 billion (Ibid., p150). Lastly, the

report surveyed 2700, High Net Worth

(HNW) collectors from US, the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Mainland

China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, and Brazil (Ibid., p257).

Within a year, the

sales total of Chen’s 3 paintings was sold for about USD 4.9 million. What does

USD 4.9 million mean for the Singapore art scene?

USD 4.9 million is

about SGD 6,564,520.67

Bibliography:

20th Century

Art Day Sale: 29 MAY 2023 | LIVE AUCTION 21394. Christie’s, 2023, https://www.christies.com/en/auction/20th-century-art-day-sale-29789/.

20th/21st

Century Art Evening Sale: 28 MAY 2023 | LIVE AUCTION 21389. Christie’s,

2023, https://www.christies.com/en/auction/20th-21st-century-art-evening-sale-29784/.

21st Century

Art Day Sale: 29 MAY 2023 | LIVE AUCTION 21390. Christie’s, 2023, https://www.christies.com/en/auction/21st-century-art-day-sale-29785/?page=2&sortby=lotnumber.

ANNUAL

REPORT FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 1 APRIL 2019 TO 31 MARCH 2020. Annual Report,

THE SUBSTATION LTD, 2020.

Evlanova,

Anastassia. Average Cost of Housing in Singapore 2023. 5 Jan. 2023, https://www.valuechampion.sg/average-cost-housing-singapore#:~:text=Average%20Cost%20of%20HDB%20Flats&text=The%20average%20cost%20of%20an,2%20and%203%2Droom%20flats.

Exploring

the Next. Annual Report, National Gallery Singapore, 2022.

Fairprice

Group. Rice. 2023, https://www.fairprice.com.sg/category/rice?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=%5BIH.000.01%2FFPon_GS_Sal_20191101%5D%20Category%20rice&utm_content=ricegeneric_RSA_+rice.

Forging

Creative Connections with the Arts. Annual Report, National Arts Council,

2022.

Huang, Lijie.

‘Gallerist Caution Budding Artists to Price Works Realistically’. The

Straits Times, 13 Nov. 2013.

Lim, Siew Kim.

‘Singapore Biennale’. Singapore Infopedia, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1363_2008-07-31.html#:~:text=The%20result%20of%2018%20months,in%2019%20venues%20around%20Singapore.

Accessed 22 June 2023.

McAndrew,

Clare. Art Basel and UBS Art Market Report 2023. Art Basel and UBS,

2023.

Singapore.

Sotheby’s, 2023, https://www.sothebys.com/en/singapore#:~:text=In%20August%202022%2C%20Sotheby's%20held,in%20the%20city%20to%20date.

The Most

Expensive Houses In Singapore - Homes Of The Mega Rich Billionaires.

Youtube, Red Potato Singapore, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gNgeV3Clzh4.

Tremayne-Pengelly,

Alexandra. Singaporean Artist Georgette Chen Sets Three Auction Records in

Less Than One Year. 1 June 2023, https://observer.com/2023/06/singaporean-artist-georgette-chen-sets-three-auction-records-in-less-than-one-year/.

Year In

Review 21/22. Singapore Art Museum, 2022.

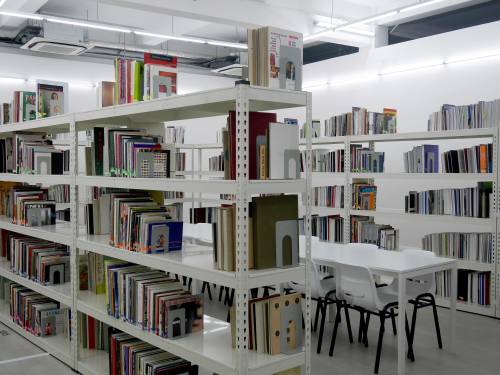

A big thank you to Grey Projects for organising Walk Walk, Don't Run, an island-wide open studio walk-about-exploration! (@jason wee aki hassan)

Walk quickly and a lot. SAW should collaborate with the Health Promotion Board and count cultural steps or steps towards culture. Give the culture vultures a reward or something, give them an artwork! Substation next inter-ministry production for SAW!

Not exactly the same but I was thinking of their earlier period in 2005 that kinda reminded me of this uk FAT. (find out more about them: http://www.fashionarchitecturetaste.com/)

Not exactly the same but I was thinking of their earlier period in 2005 that kinda reminded me of this uk FAT. (find out more about them: http://www.fashionarchitecturetaste.com/) |

| Cairns Street in Toxteth, which Assemble have helped to transform after decades of ‘managed decline’. Photograph: Andrew Teebay/Liverpool Echo |

|

| Plans for Assemble’s renovation of the Granby Four Streets area of Toxteth in Liverpool |

|

| The Cineroleum … Assemble’s first project converted an abandoned petrol station into a temporary cinema. |

|

| Folly for a Flyover … their second temporary events space was conceived as a little house trapped beneath a motorway. |

|

| Yardhouse under construction … erected with the collective spirit of an Amish barn-raising. |

|

| New Addington town square … the result of weeks of testing uses with temporary structures and events. |

|

| Goldsmiths Art Gallery … being carved out from a series of extraordinary spaces within a former Victorian bathhouse. |